Asst Professor Dr Steven A Martin

Assistant Professor of Asian Studies in Sociology and Anthropology

TREASURES OF WESTERN AMAZONIA | JOURNEY TO THE TIPUTINI BIODIVERSITY STATION AND YASUNI NATIONAL PARK

Steven A. Martin, Ph.D., Environmental Management

Where is the most biodiverse place on the planet?

In my search for far-flung places to study, I met Professor Kelly Swing, an ecologist with the University San Francisco de Quito (USFQ) in Ecuador, who believes the Tiputini Biodiversity Station (TBS) may well be that place.

Swing told me that the station's output of research marks it as a world-leading biodiversity hotspot. While there are other sites of similar importance, these do not offer the same level of access and safety for researchers.

Tiputini Biodiversity Station is adjacent to the Yasuni National Park, and together they form the Yasuni Biosphere Reserve.

Experience of a lifetime

My arrival in the Amazon town of Puerto Francisco de Orellana, Ecuador, better known as El Coca, was little short of disaster. On flying out of Quito, the Andean city nestled at the foot of the infamously active Cotopaxi volcano, we hit turbulence and heavy rain as the plane descended into the Amazon basin.

Packed with an odd mix of environmental researchers and oil workers, the 12-seat twin-engine propeller plane was forced by the weather to turn back across the mountains and the safety of Quito.

Learning there was a second flight scheduled to depart in a few minutes, I cleverly jumped in. However, this plane got delayed on the runway and the previous flight took off ahead of us, arriving first at El Coca.

Stranded in the jungle

Just twenty minutes behind my original flight, I landed at a deserted jungle runway.

Since I was not on the original flight, and in the hurry of the storm, the cars and drivers for the university and oil companies had already left.

I was standing in the middle of the Amazon rainforest, completely alone.

Moi Enomenga

The sound of the jungle grew louder as I looked around and saw nothing but trees and mud. It was my first time in the Amazon and I started to think that I might just be in serious trouble.

There was a light rain, no shelter, and the only thing to do was follow the muddy track and see where it led. But which way to go, left or right?

At that moment, a tall, strikingly confident Indian strode out from the forest and walked straight up to me.

He spoke to me in Spanish, "What are you doing here alone?"

I was half terrified, and half relieved to see someone. In halting Spanish, I explained that I was a visitor from the University, and that my car had left without me because I had arrived on a later plane than expected. I was worried he might stab me and steal my camera, but instead he offered to show me the way to the hotel normally used by the university in El Coca.

Although I was stranded for a few days until I got things sorted out, it allowed time to get to know my rescuer. It turned out that he was not just any random passer-by, but a famous environmental campaigner – Moi Enomenga, Huaorani Indian and Amazon eco-warrior.

Interview with Moi Enomenga

Amazon celebrity

Moi is an Amazon celebrity, the son of a proud indigenous leader who chose the traditional life over the ideology of early Christian missionaries. His father took his family deep into the Western Amazon to an area known today as Yasuni National Park, and so instead of learning the Bible, Moi learned deep indigenous knowledge and the cultural traditions of the Huaorani.

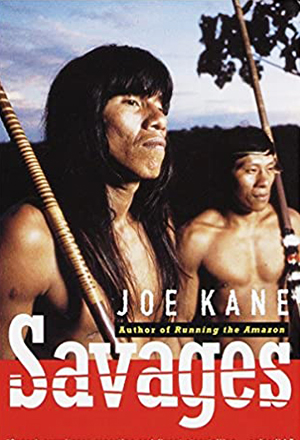

The man I met near the runway at El Coca, little did I know, was also the Huaorani jungle boy featured in Savages, a best-selling book by award-winning writer Joe Kane. Moi had matured to become a leader of the local indigenous movement trying to defend the rainforest against the oil companies.

He certainly helped me out – a total stranger in the forest.

A voice for the forest

Moi's example shows that one man who chooses to raise his voice can speak for the collective resources of the largest – and most endangered – natural habitat on the planet. Protecting the Amazon rainforest is his life's work, and the Yasuni National Park and surrounding area are testament to his ongoing success.

His recent project is the creation of a new protected area named Yame Reserve, in honor of his late father. In the light of all the growing threats to his environmental and cultural heritage, his willingness to network with tourism organizations, conservation groups, the Ecuadorian government and the United Nations offers hope to this globally vital, and profoundly endangered, natural paradise.

National Geographic | Ecuador's Yasuní National Park

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC 2012 | "Ecuador's Yasuní Park is one of the Amazon's last wild frontiers, boasting an incredible biodiversity—treetop orchids, prowling jaguars, nearly 600 species of birds—and serving as home for two indigenous nations. But a vast untapped oil supply beneath the forest floor is attracting the attention of multinational oil companies. National Geographic sent a team of five photographers, each with a different specialty, into the heart of the Amazon to document the delicate balance of life in Yasuní and how it is being impacted by the demand for oil."

National Geographic Magazine Online

Rain Forest for Sale: Demand for oil is squeezing the life out of one of the world’s wildest places

by Scott Wallis

Puerto Francisco de Orellana (El Coca)

El Coca is Ecuador's gateway to what the locals call El Oriente – the East of Ecuador, also known to outsiders as the western Amazon. El Coca is a rustic frontier town of around 45,000 people built at the confluence of the Coca, Napo and Payamino Rivers.

It was an Ecuadorian holiday weekend and I was unable to get a call though to USFQ. Given my limited time schedule, it was looking like the Tiputini trip was off.

I didn't know exactly where the Tiputini Biodiversity Station (TBS) was, and my assumption that it was "just down the river" was way off.

For several days, I explored El Coca. The Spanish I gained from studying abroad in Spain was a godsend. I met taxi drivers and boat transport services, and eventually a group of oil workers at a makeshift helicopter pad.

They told me it was next to impossible to get to TBS without an organized expedition. The oil companies and other interests had a variety of armed guards, checkpoints and road-blocks along the route. There were also the issues of traversing several rivers, and, of course, a wide range of natural predators, including snakes.

Making phone contact with the university was the only way in.

Moonlight expedition

After several days of this, I returned to the hotel one evening, and reception informed me that USFQ had called. My transport to Tiputini was arranged.

Due to my delay and problems in scheduling transport, I would have to travel to the Biodiversity Station at night. My first reaction was shock, but I figured I was in good hands with USFQ, and there was a full moon and clear sky.

It was a long night, traveling by jeep, by boat, and on foot. First we traveled several hours downstream on the Napo River to the village of Pompeya and the entrance of an oil operation.

In order to pass the oil company's security checkpoint, I needed to produce my passport and the yellow fever vaccination card, which I had gotten in Quito a week earlier. The guards at the checkpoint were armed, dressed in military fatigues, and seemed larger than life.

Next, we drove several more hours by jeep to the reach the bank of the Tiputini River, arriving at just after midnight.

The best was yet to come – we had to navigate the river, a deep and narrow channel carved through the clay that forms the Amazon Basin.

In a motorized wooden canoe, with the help of a small group of Quechua Indian guides, we powered down the Tiputini River toward the station, dodging obstacles in the water as insects pelted us in the face for two hours.

My knuckles turned white from clutching the sides of the canoe to avoid being catapulted into the river as it tilted sharply left or right to avoid rocks, branches and sand-banks.

Above, the river naturally created an opening to the sky, and the full moon was visible the entire night. The air was fresh and clean. Once my eyes adjusted, I could clearly see the river and banks in the moonlight, and I felt exhilarated to be in the real Amazon at last.

I never felt more alive.

Tiputini Biodiversity Station | Patrice Adret

Select Photos | Travels and Guides at Tiputini

Click on photos to enlarge

Learn more

If you feel motivated to learn more about the University San Francisco de Quito (USFQ)'s Tiputini Biodiversity Station, or would like to arrange for a public talk on this topic or other Learning Adventures, please let me know – I’d love to hear from you.

For study abroad, there is nowhere on earth more exciting, remote or rewarding.

Thank you.

–Steven Martin

At the request f the TBS administration, I wrote the following letters supporting public and private awareness.

Contact USFQ and TBS

Interested parties, including students and scientists, can contact USFQ for more information on joining or supporting education and conservation efforts for these outstanding programs:

- University San Francisco de Quito

- Cumbayá Campus

- Av. Diego de Robles & Vía Interoceánica

- Tel : (+593 2) 297 1700

- P.O. Box 170901

- tbs@usfq.edu.ec